Platform6Documenta11 Recently

Now and Then: Feminism: Art and History. A Critical response to Documenta XI

CloseNow and Then: Feminism: Art and History. A Critical response to Documenta XI

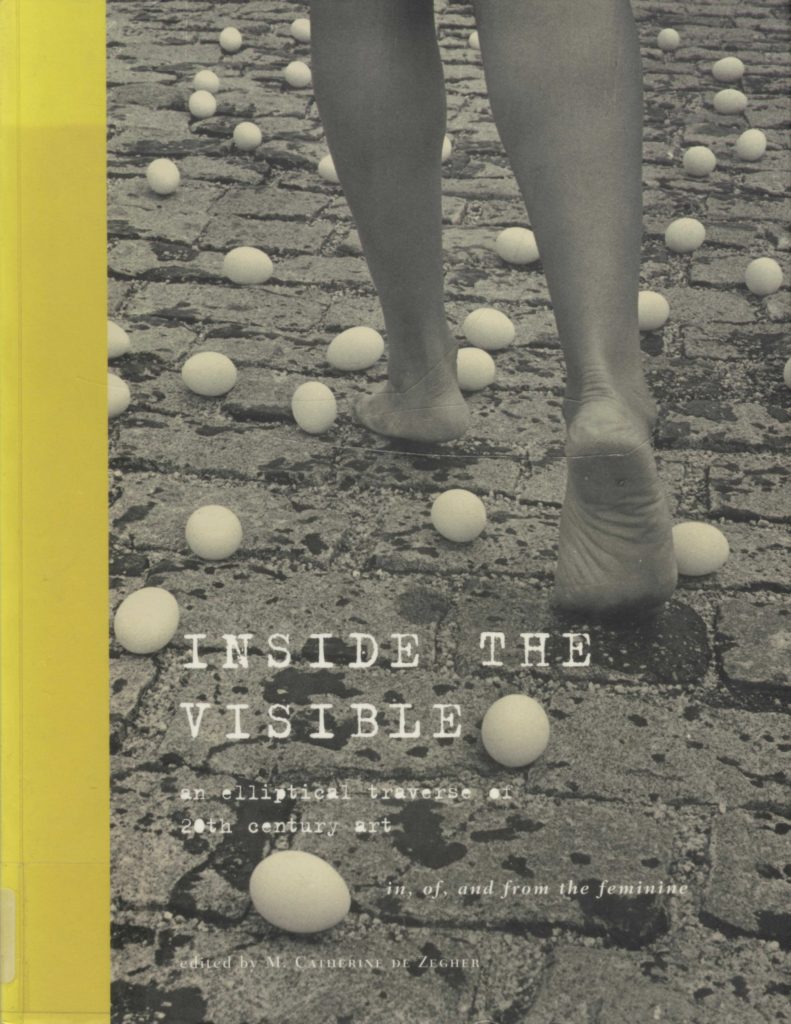

The curatorial project of Documenta XI (2002) directed by Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor challenged us to consider art practice as a way of thinking about history. The work on exhibition articulated unconsidered histories through untypical concepts of the historical accessed as the aesthetic as the site of particularity, singularity and affectivity. In many ways the project of Documenta XI was profoundly feminist, but without self-definition as such. In 1996 Inside the Visible specified an elliptical history of 20th century art 'in, of and from the feminine.' The exhibition covered three historical moments and included varied geo-political generations, orchestrating its chosen practices around the body, materiality, metaphor and language. In both cases of these strategic curatorial practices, the art works and the exhibition could be treated as 'theoretical objects.' Yet between these two events the acknowledgement of postcolonial feminism's (theory and practice) central role in structuring the ways we as producers, readers and curators think about art practices has been effectively 'disappeared': absorbed, appropriated, exnominated as a player in the field of later twentieth century cultural debate. This dialogue addresses the setting up the conditions in which the location and repression of histories of feminist engagements with the practices of art, historical analysis and of curatorial framing can emerge and be debated.

A. This is a dialogue generated as part of a debate on and response to the challenge of Documenta XI, 2002 — a composite event and continuing legacy directed by Okwui Enwezor and a team of international curators.

B. We all know that the temporary art exhibition increasingly extended to the global international spectacle has, since the middle of the last century defined the dominant mode of the circulation and knowledge of contemporary art. So what's new or even interesting?

A. Platform V of Documenta XI was indeed the usual multi-venued international exhibition of artists sited in the German city of Kassel that ran from 15 June to 15 September 2002. Its curatorial and conceptual team was composed of Carlos Basulado, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash, Octavio Zaya, led by Okwui Enwezor.

B. Let us introduce as interlocutor with Documenta XI. Inside the Visible 1996-97, a landmark exhibition in Boston, Washington, London and Perth, Australia, curated by Catherine de Zegher that was not part of the big biennial or global art exhibition circuits. It was as it were an independent and it seemed to us to mark a significant moment in an enlarged, postcolonial feminist history of interventions in and re-interpretations of the mental maps of contemporary and modern art and art history.

A. We want to measure the gap between 1996 and 2002, to show how quickly its structural feminist potential has seemed to be lost in a rapid erasure of the feminist project. What we want to explore is this: where has the legacy of feminist intervention and participation in a critical practice of theory and analysis gone? Has it been integrated into a project that no longer needs to advertise that specific dimension because it forms an integral strand of the plait or braid of contemporary concerns?

B. Are you thinking here about using Derrida's argument in Archive Fever about how an archive – a memory – can open onto a future that is not homogeneous with itself?

A. That's one way of thinking positively about the creative legacies of feminist cultural thought and practice in the very structures of Documenta XI.

B. But there is also something less positive: the question we might name, invoking Badiou's idea of fidelity to an event: fidelity means not identity or continuity but a continuous performing and thus actualising of an event that only becomes effective in that fidelity of engagement so that the event –1968, feminist politics or whatever that causes change is not commodifiable as an entity which can be -ism-ed, dated and then safely put back on the shelf as past its sell by date.

A. This takes us to the heart of Documenta XI's project: as we see it: how to re-invent, and significantly develop, in and through the sphere of cultural practice in an enlarged and intellectually interdisciplinary space, the practice of politics: a hope for change, a continuing criticality vis-a vis the challenging situations of what Friedman defines as our dilemma: we inherit modernity without modernism: we inherit both the emancipatory aspirations and ambitions of democracy and rights and the catastrophic and vile dimensions of colonialism, racism and genocide that we can no longer misread or analyse through the terms of political of cultural analysis that modernity initially proposed.

B. This makes the exhibition move out of the space of mere cultural entertainment and big art business into the realm of history and politics, precisely re-conjugating relations between art, history and politics but in novel forms.

A. We could say that feminism marked a historic development of such an attempt. Framed by its own specific address to a variety of questions that no other politics had brought to centre stage, feminism certainly challenged the traditional modernist concepts of the political and cultural that it inherited.

B. But there is a real confusion at the moment in the way feminism is being shuffled off the historical stage. On the one hand, people accept that feminism was a historic address to the repressed question of gender, raised by a political and a theoretical practice since the 1970s to a level of sustained social, cultural and political theorisation and analysis that has changed the social, economic as well as cultural discourses. This attention to gender as a continuing axis of domination and oppression world-wide has been integrated into complex fields of cultural analysis and social policy as one element of our configurations as social subjects in capitalist and postcolonial worlds. Feminist practice is an element but an important one in what is offered about the politics of the personal, the body, the subject, and relations of power operating through these hitherto under theorised locations and relations. Foucault's bio-politics or life world politics is you like.

A. On the other hand, from a longer and trans-cultural perspective, what we can name feminist thought, even if itself did not have such modernist self-definition, marks the structural problematic of sexual difference in human culture and history – what Kristeva tried to think about under the rubric of women's time: the time of sex and desire and creation. From a feminist perspective, sexual difference is more than social gender, for it works imaginatively and symbolically to think and rethink the structurings of difference, with the paradigm of sexual difference investing other historical and social relations of difference with its complex relations to eroticism, sadism, identification, horror, phobia, abjection and so forth. Sexual difference is not about women. It constitutes a specific area of feminist interest since sexuality and sexualisation are bound to the constitution of subjects in terms of difference in relation to what Freud called 'the sexual functions' that dimension of human subjectivity between eroticism and death. As Homi Bhabha stressed in his analysis of colonial discourse in his reading of both film and Fanon, we are always caught simultaneously in several economies at the same time: governmentality and desire. To catch the relations of power we must think in what he called a spiral of difference that moves constantly rather than a hierarchy in which gender can be isolated and fall away from more pressing questions.

B. So what you are saying is that certain historic feminist practices have fed into the new formulations of the relations between the aesthetic and a politics - it has been a creative legacy that needs to be acknowledged even if the forms of their enactment have enlarged and become inclusive.

A. I am also suggesting that there is a danger of throwing the theoretical baby out with the historical bathwater and losing sight of the continuing importance of analysing and specifying sexual difference as a structure of human meaning-making and social imaginaries that is constantly at play even in areas not defined as a feminist problematic.

B. Let's get back to the exhibition platform. I visited that exhibition in July 2002 for the few days I could afford. I was immediately struck by the importance of what it was setting up qua exhibition but also in an extended engagement with contemporary art world politics and politics – history on a larger scale that could not be contained as merely event and exhibition.

A. I found it significant that Documenta XI consisted of five platforms in total. Its concept extended beyond the usual diet of exhibition as entertainment with related academic or critical events. As a whole the project performed a more complex interrogation of the conditions of our experience of and the places allotted to contemporary art practice as a critical engagement with contemporary history and the radical changes to the world since 1989.

B. What is significant is that these platforms are now archived as books that mean something of the eventual structure is lost but something else is opened onto the world, namely wider discussion of their engagements. In the single Preface that opens each of the five publications with a common statement we read a sentence that directly conjugates the political and the cultural.

A. We have so often been told that the separation of the spheres of Aesthetics, Morality and Politics is the hallmark of cultural modernity while they were constantly drawn into complex relations by those dissident theorists and practitioners unwilling to comply with separation of spheres favoured by the modernist bourgeoisie - intent always on destroying politics altogether as a dynamic instrument of change and contestation.

B. Secondly, we read in the Documenta preface of collaborations between artists, scholars, thinkers, activists, curators. Again rather than maintaining professional distinctions against whose dividers the marginal and oppositional thinkers, artists, curators and activists have struggled, often in vain, in institutions and public policy, Documenta XI staged their collaboration in an attempt to conjure up for a moment the lost possibility of a public sphere. So let's read out the statement:

The framework within which this takes places has both political and aesthetic objectives. But rather than subsume the concerns of art and artists into the narrow terrain of Western institutional aesthetic discourses that are part of our current crisis, we have conceived of this project as part of the production of a common public sphere. Such a public sphere, we believe, creates a space whereby the critical model of artists, theorists, philosophers, historians, activists, urbanists, writers and others working within other intellectual traditions and artistic positions could productively be represented and discussed. The public sphere imagined by these collaborations is to be understood then as a constellation of multi-faceted platforms in which artists, intellectuals communities, audiences, practices, voices, situations, actions come together to examine and analyse the predicaments and transformations that form part of the deeply inflected historical procedures and processes of our time.

Enwezor, Platform1: 11

A. This practice furthermore, and I quote: 'inscribes within the exhibition project itself a critical interdisciplinary methodology that is to be distinguished from interdisciplinarity as a form of exhibitionism.' (Ibid).

C. I would like to work on this statement for a while. Within the exhibition project is inscribed an openness to, if not a necessity for, extension into and collaboration with other practices disciplines, habits of thought and sites of their creation and dissemination. This porousness, or what we at CentreCATH conceive of as transdisciplinary encounter, can only be realised performatively. The team insist that what they are doing is the opposite of an institutional display of merely spectacularised interdisciplinarity which may bring representatives from different disciplines together in an often-incoherent display of variety. Such a display is merely an image, in contrast to creating a space for the work of a critical interdisciplinary methodology that addresses itself to the work that must be done by the co-productivity or shared praxis of the encountering parties whose outcomes co-emerge in this politicised poeisis.

A. Hence the importance of the reinvention of a critical public sphere, created in the infrastructure of both platform - encounter and event - and text - inviting others to participate in their own activities of reading and discussion that extend the webs of connection and recognition of shared concerns, even if differing interpretations are offered for the deeply inflected historical procedures and processes of our time.

B. This leads me onto the statement that the space of contemporary art and the mechanisms that can bring it to a wider public domain require radical rethinking and enlargement. This is not merely a matter of scale but is about defining a socio-political geography that reminds me of what Martha Rosler wrote in her analysis of onlookers, audience and publics in her essay ‘Lookers, Buyers, Dealers and Makers: Thoughts on Audience (1979). As she says ‘there are certain relations that must be scrutinized if anything interesting is to be learnt about the disjunctive relations between artworld audiences and the public sphere.

A. I am interested in the use of metaphors of space and its imagined or real enlargement, and in spheres and their political expansion if not reinvention. This is indicative of a deeper epistemological shift from modernist temporality and linearity to postcolonial lateral spatiality. It also ghosts the socio-economic transformations of capitalism in its new globalized and unchecked imperialism. Thirdly, it registers in its Imaginary the material effects of our double condition of postcoloniality and globalization that involves us in registering movement, translation and circulation that contain both the lineaments of and the alliances of resistance.

B. In his famous essay on 'Postmodernism and the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism' Frederic Jameson identified the post-modern with a waning of historical depth accompanied by a convenient political amnesia. The synchronous space of the spectacular present becomes unhinged from its momentariness as the ever fragile leaf between its past and the becoming future onto which it endlessly opens. So the Documenta XI project seems to be trying to invent a means of addressing the non-linear history of the present.

A. The present is, by virtue of the doubled condition of globalising capitalism and deterritorialising postcoloniality not merely spatial at the cost of losing a sense of history, of time, but spatial as a means of recapturing what Marx called the totality of many relations and determinations that in the rapidity of the remapping that took place in the last decade of the last century presents us with a demand for increasingly spatial concepts with which to theorise and analyse and thus to work politically upon what is happening in the concrete of social relations.

B. Are you thinking here of Zygmunt Bauman's work of camps, encampments, nomads, tourists and other images - and Paul Gilroy's recent work between camps?

A. Politics is the struggle for and in history; the name we give to our responsibility as historically conscious citizens rather than the benighted consumers into which Zygmunt Bauman writing already in the mid 1980s saw western governments willing us all - in the process creating the condition for the exclusions from membership of society of those without a credit card.

B. The very subjects of Marxist history according to a discredited socialist narrative - the oppressed, exploited, emiserated and undernourished, whose relief and liberation had been the goal of modernist socialist dreaming were now declassified: no longer the mobilising class of radical change, and no longer party to the substance of the managed consumer society. The oppressed and exploited are rendered merely the abject of global capitalism in the absence of a political narrative redesigned by those very conditions of transformation.

A. What Bauman has named 'wasted lives', also links us back to Hannah Arendt's analysis of totalitarianism's deep crime and continuing threat: to render humans superfluous.

B. Classification and enclosure in the barrios, ghettoes or refugee camps takes the place of the relations of class. The bureaucratics of modernity replace its dynamic plays backwards and forwards across several territories and constituencies linking this strange effect with a more deadly capacity or appropriation by the right to name and denominate that marked the genocidal horrors of the twentieth century. The post-modern erasure of the political makes class, gender and race relations unnameable even while intensifying these axes as means of domination and exploitation.

A. It is not surprising to find that of all the embodiments of a modernist agenda for equality, justice and change, those concerning fundamental relations of oppression and exploitation like socialism and feminism fell from favour in the postmodernist 90s, acquiring the bad smell of the fusty, old-aged and irrelevant in face of the pacey, smart, cool rapidly changing surfaces of a world marketplace occupied only by self-fashioning consumers.

B. Documenta XI marks in the sphere of art practice and art history - our sphere of particular interest and responsibility - a contribution to what can only be considered an encouraging fight back by intellectuals, scholars, artists, and activists to re-imagine the means of confronting the still unfinished business of the catastrophes of modernity and the West's hopefully brief hegemony.

A. During the 1990s a series of conferences, publications and exhibitions performed the end of century and further end of another Christian millennium reflected on the twentieth century asserting it to have been one of the most consistently violent and traumatic of known history.

A. 1996 was the year of a Paris-based block buster titled Face a l'Histoire which plotted the relations between art and history from 1933-1996 using a central column of newspaper and photo-journal witness to war and violence as the backbone from which the ribs of individual artists' responses could be artistically plotted.

B. That same year Catherine David was planning what would become Documenta X held in 1997. It would take seriously its role as the last Documenta of the twentieth century and look back to a post-war history charted by four dates: 1945 – the foundation of post war European democracies; 1967 – a radical crisis of this post war settlement; 1978 – marked the already considerable advance of globalising capitalism and the repression of oppositional thought; 1989 marked German reunification, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the triumphal celebration of a post-modern aesthetic. All of the processes thus dated leave a legacy of increasing uncertainty, including fading of the nation-state, 'neo-colonial relations between economic centres and the fractured multitudes of the peripheries', opening an era of conflict and multiplication of an ersatz politics of identity 'as vectors of consensus and conflict across the world.'

A. What makes Documenta XI different, significant and worthy of attention in this context?

B. Its structure as a performative engagement with more than analytical identification of the changing landscape of the global or post-modern. Thus its other four platforms began to map the terms of a politicising, demythicising analysis of the present significantly pivoting the centres of discourse.

A. Democracy Unrealised was held in Vienna 15 March- 20 April and 9-30 October 2001

Within all these transformations, crucial to the narration of modernity in our time and the formation of subjectivity (ethnic or national, individual or collective) an important qualification needs to be made, which is the extent to which current tendencies of democratic governance are inherited from or connected to the traditions of Western conceptions of democracy. Because it cannot be denied that the state of democracy around the world today has become more varied and flexible, we are moved to question whether the notion of democracy can be sustained only within the philosophical grounds of Western epistemology. What are the possible ways to imagine democracy today as method and praxis available to both governors and governed, nation and subjects alike?

B. Experiments with Truth, Transitional Justice and the Process of Truth and Reconciliation was held in New Delhi 7-21 May, 2001

Using as title the title Mahatma Gandhi's autobiography, this panel addressed itself to the scars of violence, genocide and trauma that are the underside of the hope of rights and justice that may or may not be served by the juridical as well as social processes of truth and reconciliation commissions which become the courts of history as well as laboratories for social reconstitution.

A. Creolite and Creolisation took place on St Lucia 13-15 January 2002

Based on the Caribbean island home to the poet Derek Walcott, this platform took its lead from major debates within the intellectual and artistic communities of the Caribbean that Stuart Hall defined as the primal scene of a tragedy in the matrix of which the negotiations between what he terms the presence africaine, presence europeenne and presence americaine are in a constant state of productive transformation. The introduction declares:

In recent years the increased and accelerated process of cultural mixing around the world have produced new configurations of identity. Flows of images and cultural symbols have occurred across a geographical space reconfigured along specific pathways. Rapid, unceasing and often violent cultural encounters have created a context of uncertainty and unpredictability in which old symmetries are irrelevant.

The notions of hybridity, metissage and cosmopolitanism have been deployed and reworked in order to capture polycentric and polysemic aspects of these new configurations. While still relevant, the notions of hybridity and metissage under pressure from local resistance no longer seem adequate as vectors through which to understand and articulate critical issues of difference and the asymmetry of contemporary culture today.

Under Siege: Four African Cities: Freetown, Johannesburg, Kinshasa, Lagos, and took place in Lagos Nigeria. 16-20 March, 2002.

The African city raises major issues of modernisation, development and postcolonial citizenship. The question posed here was formulated thus:

How do today's African urbane discourses respond affirmatively and critically to the changes in the colonial city, as postcolonial urban imagination – wittingly and unwittingly – continues to overwrite the hard-edged colonial formalist distinctions that established an epistemological division between urban and rural, tradition and modernity, formal and informal, village and city, authentic and inauthentic, chaotic and orderly?

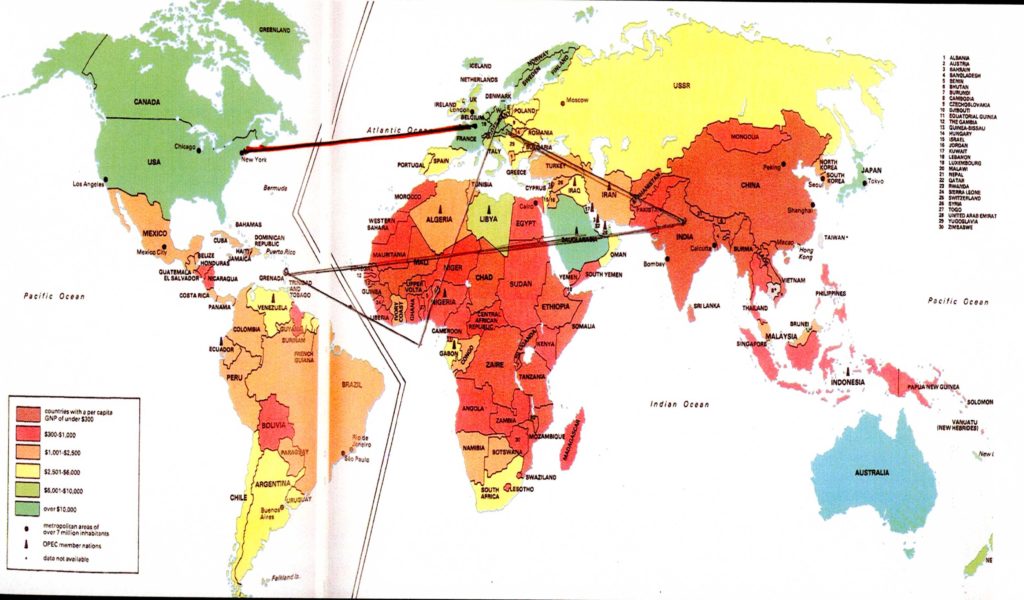

A. Let us consider the virtual map created by the lines between these five events. I found this useful map colouring in the countries according to their place on a scale of wealth.

B. We start in Vienna, the heart of the old Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire – hence the heart of Modern Europe – and the more recent site of the 1938 Anschluss which linked the capital of Austria to the most heinous of twentieth century Imperialisms: Greater Germany of the Third Reich.

A. We then travel to the north of the subcontinent. to Bharat, India, to one of the most ancient civilisations of the world, the site of many overlaid imperia that achieved its status as the world's largest democracy only in 1947 with its independence from the last of its several foreign rulers, the British Raj or Empire, the home of Mahatma Gandhi.

B. We then swing back from traversing the bulk of sub-Saharan Africa to cross the Atlantic, marking in that movement over that ocean that most egregious horror of the middle passage to a New World, that was for those inhabiting it an old world, their world, suddenly to become the only world of transported and enslaved Africans mixing with indigenous Caribs whose name remains now as a cartographic marker for a holiday playground for the wealthy but also the home of major cultural thinkers and makers of whom Frantz Fanon is merely one of many. St Lucia marks an island country lodging these complex and painful histories of slavery and colonialism between the mighty spaces of old and new empires on the South and North American continents, while being bound by history back across to the third point on the triangle that forms what Paul Gilroy named 'the black Atlantic'.

A. Thus we move back across that same ocean but to the South and to another continent of ancient and varied civilisations, to rest in Lagos, a massive city in the vast country of modern Nigeria, that like India, was carved out of its ancient histories and reworlded in the epistemic violence of British colonisation and neo-colonialism. Lagos becomes the place for meeting for a continent wide discussion of urbanism and experience bloodily marked by the knife wounds of colonial cartographies and the struggle for self-fashioning in relation to justice, democracy and rights being rewritten at the intersection of trauma, history and tradition, experiments not only with truth and with justice, we remember Ken Saro-wiwa and the suffering Oguni people but of modernity and its urbanities.

B. It has been a commonplace of recent art history that the axis of what was legitimated and curated for history as modern and contemporary art runs in a fine and abbreviated line between New York, London, Paris, Berlin with extensions to Venice and Kassel and perhaps, to Sao Paolo. A challenge to the Euro-American hegemony was mounted at first by the initial moves of postcolonial thought that identified a centre-periphery dialectic. From this moment we inherit significant terms of analysis and politics of cultural practice.

A. As Chilean-based cultural critic Nelly Richard wrote in 1987/88, significantly in the second issue of the critically significant journal Third Text, in an essay exploring the potentiality of the post modern for the so-called periphery, early analyses of these relations confronted the monolith of a homogenising modernity which was in addition identified – she quoted the late Craig Owens – with the privilege of Western patriarchal culture which suppressed any notion of difference that might challenge the dominant model of subjectivity. Modernity worked towards consolidating this unity of privilege.

B. Richard states:

Transferred to the geographical and socio-cultural map of economic and communicational exchanges, this fiction [of the unity of the Modem] operates to control adaptation to given models and so to standardize all identifying procedures. Any deviation of the norm is classified as an obstacle or brake to the dynamic of international distribution and consumption. Thus modernity conceives of the province or periphery as being out of step or backward. Consequently this situation has to be overcome by means of absorption into the rationality of expansion proposed by the metropolis. (Richard, 1978/88:6)

A. What I want to pick out here is the clear linking of the critique of the metropolis and the critique of what was then named western patriarchy, both of which performed a unification against difference or ambiguity offering only the false lure of assimilation – equality – into its attractive privilege as the way out of secondary or backward status. This links a feminist critique and a post-colonial critique from a perspective of seeing the common margin and the need for more than one mode of analysis to catch the imbrication of socio-economic as well as symbolic structuration of power relations.

B. We have been amply warned, however, of the modes of appropriation and cultural management of the critique of Euro-American hegemony. Jean Fisher's stringent editorial to an issue of Third Text in 1996, entitled 'Contaminations' already introduced new terminologies and modes of analysis, reflecting back on the dilemmas to almost a decade of struggle against western domination and self-centralisation. Negotiating the shallows of new essentialisms, nationalisms and exoticisation of difference, that appeared to challenge the model of the One Richard identified, Jean Fisher argued:

At the same time, for black and non-European artists to allow themselves to be promoted through commodified forms of ethnicity is for them to be complicit with the western desire for exotic separatism. The exoticised artist is marked not as a thinking subject in its own right but as a bearer of pre-determined cultural signs and meanings. To be locked into the frame of ethnicity is also to be locked out of a rigorous philosophical and historical debate that risks crippling the work's intellectual development and excluding it from a global market where its understanding of the world might add to the knowledge of the world. Indeed one might ask if art can develop unless it enters a public discursive space where it can measure itself against what is currently regarded as most vital to the spirit of the age. For better or worse the western metropolis has been the place where money and energies and so ambitious artists have gravitated. But it has also been necessary to create a place from which it has been possible to speak. (Fisher, 1995:5)

A. This last sentence should cause us to pause for a moment: Jean Fisher calls for a place from which it becomes possible to speak, not as a representative of a defensive or imposed and commodifiable exoticised identity but as thinking party to a rigorous philosophical and historical debate taking place in a world public discursive space that might produce knowledge of the world from located understanding of the world.

B. Fisher's terms anticipate and re-echo, lending their already articulated weight to the ambition of the Documenta XI team to create platforms of critical thought embedded in the major historical and philosophical debates of our clashing worlds without centralising the machinery, terms or personnel in the hegemonic west.

A. This text by Jean Fisher was partly related to a symposium organised at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Boston, USA, held to initiate the programme that would culminate a year later in the exhibition Inside the Visible, curated by Catherine de Zegher, based on a series of exhibitions she had curated in the Belgian city of Kortrijk, drawing into significant pairings a series of artists from Latin America, Cuba, Korea, Europe, America and Japan.

B. Inside the Visible was for us an exemplary attempt to use curation and exhibition practice to challenge modernist and colonialist notions of art, time, history and significance by remapping the century's cultural practices from its cultural and geographical margins. The exhibition's curator proposed that 'difference is far more entangled and complex than we like to admit' and Catherine de Zegher continues: 'Taking this into account, I have attempted to develop an exhibition concept that bypasses the artificiality of "oppositional thinking" while acknowledging the work of deconstruction, feminism and post-structuralism, which has been instrumental in revealing the operations that tend to marginalise certain kinds of artistic practice while centralising others.' So we see her thinking with feminist theory in order to produce a different pattern of dissidence and situated singularities on a global map of artistic practices.

A. The exhibition Inside the Visible an elliptical traverse of twentieth century art was significantly subtitled in, of and from the feminine. That all the 39 artists were in fact women was both highly significant and normalised to a point of insignificance. In that grouping that was international each became a moment of generational/geographical singularity. The exhibition staged the complexities of difference in which the false isolation of gender was avoided in favour of a careful plotting of overdetermining relations of difference and convergence at the level of history, practice, and dissidence in which the historic contestation over the term, the feminine as predicament, possibility or psycho-linguistic position active within all local contexts played in fields of political, geographical, cultural and sexual embodiment and poetics.

B. Jean Fisher and Catherine de Zegher were joined on this pre-exhibition panel by Martha Rosier, an artist whose practice over almost forty years has not only interrogated the conditions of production and distribution of art, but has also examined the very conditions of quotidian knowing, and indeed unknowing in which art may be complicit or critically active. Martha Rosler's long career has been a conjoined practice of work and analysis refusing the false marketable separation of thought from practice, political understanding from aesthetic knowing.

A. What we wish to focus on is a reading of the theory and practice of Documenta XI as a decisive intervention in this accumulated history of cultural responses to and interventions in the conditions of cultural practice and consumption in relation to the diverse political, theoretical and artistic practices upon which its conceptualisation and realisation is built.

B. Yet where and how does feminist inflection play in this re-envisioned field of a cultural politics not from the centre? Is its legacy in rethinking the political in cultural practice being rendered unspeakable because of a mistaken bonding of its histories to First World thought? Is it honoured in the inclusion and repressed by the same token although its erstwhile partners remain in the field of acknowledged discourse and practice? Is this the grounds of a new politics of exclusion and why?

A. Put simply what happens if we measure the distance between 1996 and 2002 in relation to the fate of one thread in this complex plait of cultural theory and practice: the feminist intervention, so clearly imagined as a partner in the emergence of the critique of modernist, universalist, Eurocentric unity in the early formation?

B. One can continue to question: How does gender inflect the histories and processes of African cities in the light of recent statistics of the vulnerability to aids infection and premature death because women's subordinated position prevents them from insisting on protected sex?

A. What of the discussions of the maternal and women's informal relations to language in the debates about créolité and créolisation?

B. What of the trauma trials of truth and reconciliation in former Yugoslavia where rape was a regular instrument of ethnic warfare and dehumanisation?

A. What of the struggles for redefining democracy within and beyond the nation state, the liberal polis – was it not the women's movement that with its co-dissidents of the 1960s and 1970s redefined the political, challenged the divisions of the public sphere and the private domain, locating politics in the intimacies of human relations and made issues of violence and abuse as much as education and employment major platforms for women's human rights?

B. When Zygmunt Bauman, one of the most prolific of current social analysts, identifies the translating of private troubles into public issues as the condition of the renewal of politics today, are we not hearing unnamed, however, the deepest impulse that defined what feminism does?

The full quotation from the back of Bauman's In Search of Politics from 1999 is:

What is at stake in this enquiry is the possibility of rebuilding the 'private/public' space where private troubles and public issues meet and where citizens engage in dialogue in order to govern themselves. Individual liberty can only be the product of collective work, it can only be collectively secured and guaranteed. And yet today we are moving towards a privatisation of the means to secure individual liberty. If seen as therapy for the present ills, this is bound to produce effects of a most sinister kind. The art of translating private troubles into public issues is in danger of falling into disuse and of being forgotten. The argument of this book is that making the translation possible again is an urgent and vital imperative for the renewal of politics today.

A. Documenta XI's idea was that 'the space of contemporary art' needs a radical rethink and enlargement to bring it to a wider public domain – hence the Platforms. In the generic preface to all the platform books the curators declare that if there is a politics of any kind to be deduced from the platform framework, it is one of 'non-ambiguity, and the idea that all discourses, all critical models (be they artistic or social, intellectual or pragmatic, interpretive or historical), emerge from a location or situation, even when they are not defined or restricted by it,' and that they have, above all, been attentive to how contemporary artists and intellectuals begin from the location and situation of their practice.

B. Sound familiar?

A. The core text for me would be Donna Haraway's essay "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective" that was first composed in 1986. Reclaiming the 'much maligned system: Vision' Haraway, of course insists on the embodied nature of all vision in order to counter the conquering gaze from nowhere that sees without being seen, and represents without being represented and marks all other bodies without being marked. The unmarked position is that of Man and White. In order not to flim-flam into the mire of subjectivity and identity, Haraway calls for a feminist objectivity – a feminist politics of knowledge based on situated knowledges.

She wrote:

A commitment to mobile positioning and to passionate detachment is dependent on the impossibility of innocent identity politics and epistemologies as strategies for seeing from the standpoints of the subjugated in order to see well. One cannot 'be' either a cell or a molecule - or a woman, a colonized person, a labourer and so on, if one intends to see and see from these positions critically. 'Being' is much more problematic and contingent. Also, one cannot relocate in any possible vantage point without being accountable for that movement. Vision is always a question of the power to see and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualising practices. With whose blood were my eyes crafted? We are not immediately present to ourselves. Self-knowledge requires a semiotic-material technology linking meanings and bodies. (Haraway, 1991:192)

A. So in this process of locating what it is we are doing here we should be absolutely unambiguous.

B. One of us experienced Platform5, visiting the exhibition in Kassel in September 2002 as a necessary element of a studio-based teaching practice between art, history and theory,

A. One of us has a more theoretical relation to the overall project as represented in its published forms: events that now live on as texts, open to other readings and only virtual encounters and dialogues which relate to CentreCATH's insistence on research as process and encounter rather than commodity.

B. What was striking about the exhibition in Kassel was how much of the work involved the activity of thinking about history, about what counts as worthy of historical investigation now, in the case of Chantal Akerman's real-time video broadcast and On Kawara's live performance, quite literally minute by minute, and it challenged the visitor to consider ways in which art 'does' history in material and aesthetic terms.

A. As such it registered a significant change in curatorial approach to that of Documenta X, Pol(e)itics, 1997 typified by the statement of the editors about the aim of the accompanying book.

This book seeks to indicate a political context for the interpretation of artistic activities at the close of the twentieth century. It contains little art criticism as such, but instead engages in a confrontation of images and documents from the immediate post-war period. The range of material treated here is not encyclopaedic; it represents a polemical attempt to isolate specific strands of artistic production and political endeavour which can be taken as references in the contemporary debate over the evolution of our societies. Drawing from distinct yet interrelated territorial and linguistic domains, the book singles out complex cultural responses to global modernity... The material has been organised chronologically, around the articulations provided by four emblematic dates in contemporary history. 1945,1967,1978,1989.

B. Here a political context for the 'interpretation of artistic activities' is established in advance of what the artworks themselves might propose as political activity/thought. The organising chronology is pre-determined by the dominant Eurocentric narrative of what count as emblematic dates in contemporary history. And, significantly, the aesthetic structure of the book is 'montage' – between work, document and commentary.

A. The curatorial project of Documenta XI seems to register precisely the shift in contemporary art practice away from the dialectical technique of montage (in its strict Eisenstein-ian sense) in which images and texts are wrenched from the particularity of their situation to be mobilized in a dis-located practice of polemical argument, towards what we might characterise as a form of indexicality at several levels.

B. One of CentreCATH's research key themes is the ethics or the politics of virtuality and indexicality, the latter being a way of holding onto a sense of the material determinants of Marx's categories of the social relations of production that Haraway's vision of socialist feminist cyborg culture so strongly retains and it also hold onto what was proposed by viewing art through the doubled axis of generation and geography: location in historical time and socio-cultural space.

A. Since all acts of representation occur in and indeed create the poetic possibilities of the virtual as a release from the actual, and since all acts of representation however virtual are also actual, effectual and actualising through the functions of the imaginary and the symbolic that defines subjects and its meaning, we need to overcome false oppositions such as real and virtual through accepting the semiotic locus of the indexical as a means of holding together a sense of social economic materialities, embodiments and affects and the determinations otherwise by signifier and unconscious.

B. Your definition of a politics of indexicality helps me to get a purchase on what happened with Ulrike Ottinger's Southeast Passage. AJourney to New Blank Spots on the Map of Europe, 2002 in the space of the gallery. It is a film in three parts, parts: 1. (130 mins) Wroclaw-Varna, 2. (140 mins) Odessa, 3. (90mins) lstanbul. This makes a total of 360 minutes of film time. Would a visitor to platform 5 be prepared to spend the full six hours with Ottinger's footage when there was so much other work to look at? Not likely. I had only two days to 'do' Documenta and watched 30 minutes of the Odessa section. In that time people moved in and out of the room at intervals of between one or two and 15 minutes. I watched footage of traders and shoppers in a meat market in Odessa where every part of the beast was displayed and for sale in huge chunks and tiny scraps that hardly looked fit for human consumption. Then cut to some activity with ropes and rusty winches on deck filmed from the bridge of a rusting ship docking -or departing? Next, conversations between the members of two fleeing Romany families camping in disused railways carriages in a wood; sound diegetic, ambient, no voice-over to narrativize what there was to be seen and heard. I'm being as carefully phenomenological as I can with this description, also aware that memory has its own phenomenology, that the recounting of an encounter with any work is itself always a story that remakes it.

A. Yes, but you started out talking about Ottinger's film because you wanted to make a point about the value of the concept of indexicality for trying to make some sense of it.

B. I need to come at the film again, from another direction, but still located in the experience of visiting Platform 5. In terms of the sustained attention that each work demands documenta is vast and time consuming. Most visitors are pushed for time.' We didn't get to see everything' is the common lament of the returning Documenta goer. Most have to make a choice about what to see. So buying the catalogue first is a good idea. Ulrike Ottinger has been making films that have engaged with issues of gender, sexual and cultural difference in various engagements with documentary, mainstream narrative and art film since the mid 1970s. I want to see her latest work. Under the heading Southeast Passage. A Journey to New Blank Spots on the Map of Europe, I read:

The moving image of the film follows the movement of the journey, the geographic thread leading through southeast Europe from Berlin through Poland, the Czech Republic, and the Slovak Republic, over Romania and Bulgaria to the Black Sea. The journey continues by freighter to Odessa into the Ukraine and from there along the coast to its South-eastern endpoint, Istanbul. It shows streets, markets, villages, cities, and architecture. The encounter with people and their places give rise to cinematic miniatures. These contrast with and the new and the old almost imperceptibly; they give hints, subtly or outspoken... What is brought up are no longer the old "heroes of the working class" but the new heroes and heroines in the struggle for survival who use their great courage and inexhaustible imagination to get by. They are also the ones who make the invisible borders passable. We encounter these new nomads (who were once teachers, lawyers, farmers, manual labourers) as the conduct their business at the barricades of the many borders, at the edges of sasmll and middling streets, in almost abandoned ghost towns of the rural areas, in the small markets and bus stations.

A. So this is documentary of a sort then?

B. Well let's start by saying that, having read the catalogue summary of Ottinger's project and what emerged from it, I went into the screening room with an idea of the overall shape of the film.

What puzzles me now is the status of my 30 minutes with it.

Some questions immediately arose. How long had the film been running when I entered the room and what had I missed? Where, geographically, on the journey on which these images/sounds were recorded was I when I walked in? How long could I afford to stay given that I had so much more of the exhibition to get around. What would I miss if I left – certainly I would fail as a witness to the emergence of the new class of nomads struggling for survival in places beyond the interest of the media that the catalogue tells me is the cumulative effect of the film. But I can't stay for six hours. I feel irresponsible for shuffling out after only 30 minutes, into what in my memory (though probably not actuality is the long narrow corridor thronging with visitors along which is installed above head-height 13 video monitors playing 13 episodes of Nunavut (Our Land), 1994-1995 made by the Inuit production company lgloolik lsuma an simultaneously. The crush of the crowd propels you along the corridor. If everyone stopped to watch the entire 28 minutes of a single episode there'd be a major bottleneck.

A. We haven't time here for you to go on with this kind of description.

B. I just need enough of it to make a point about the value of your particular definition of indexicality: as 'being a way of holding onto a sense of the material determinants of Marx's categories of the social relations of production', which the Documenta idea of a politics of 'nonambiguity' is also an echo. I saw enough of Southeast Passage. A Journey to New Blank Spots on the Map of Europe, to get the gist of the project overview that the catalogue had provided me with. But what also became apparent in the encounter with the film at platform 5 was precisely the material determinants of the relations that functioned to produced it as a different object for the viewer in the actual exhibition situation.

A. Mark Nash, in his essay in the catalogue for Platform 5 asks whether the new physical mobility that the spectator is offered when film is installed in galleries and museums really involves a critique of dominant spectatorial regimes of cinema? 'Do they explore the discontinuities inherent in spectatorship, in the sense that Homi Bhabha defines it, as an overcoming of binary oppositions and opening up a "process of translation"'.

B. For me his questions touch upon feminist histories at several points. Trinh T. Minh-Ha's film Naked Spaces, Living is Round made in 1985, which I saw for the first time in the late 1980s in a cinema in Perth, Western Australia was installed in the gallery in Platform5. Historically a precursor and resource for Ottinger's experiments with documentary and central to which was the role of duration, the 135mins of Naked Spaces itself now was subject to a process of translation - to encompass a variation on the elements I noted in the encounter with BS which did not arise for naked space in the cinema in the 1980s. Trinh's 1989 film, Surname Viet: Given Name Nam, exemplifies what Nash in his essay refers to as her 'feminist and anti-ethnocentric gaze'. It concretises the subtlety and rigour necessary to perform a "process of translation" precisely in Homi Bhabha's sense at the juncture of the categories 'Woman, Native, Other', already a conjunction that challenges the Wes/Other binary. No doubt the African location of Naked Spaces played a part in the choice of this film by Trinh, reflecting the interests of Documenta 11's Director, Okwui Enwezor. Yet in this film the centrality of non-Western feminist politics to post-colonial histories and art practices are not explicit.

A. As Martha Rosier commented in the context of Art Forum's roundtable debate on the Global Exhibition: 'I liked Okwui's (geopolitical) discourse-heavy approach at Documenta very much; but it allowed the unavoidable residue of absurd inclusions and puzzling exclusions to stand out glaringly for all to see'.

B. This leads to my second train of thought triggered by Mark Nash's essay. While writing this introduction I became aware of and anxious about the fact that what I had to say about the experience of Documenta11 centred exclusively on lens based and digital translations of lens-based work.

A. Nash's argument seems to be that 'moving image practices and the critical and theoretical debates surrounding them have transformed the space of contemporary art and curatorial practice.

B. He recalls a moment, the 1970s -1980s in Britain when film was at the centre of the development of theoretical debates on cultural production; The Edinburgh International Film Festival Conferences from 1970s until 1986, and in the pages of Screen Magazine. His comment that Screen had been unable to extend its thinking from psychoanalytically inflected discussions to broader questions of cultural difference is a valid observation. in this context, however, it functions to undervalue the legacy in Documenta11 of feminism's ground-breaking work on the imbrication of subjectivity and spectatorship.

A. Your experience of Platform5 does, however, seem to bear out his argument that again the moving image is the critical focus of a range of contemporary, and significantly, collective and collaborative practices, historical practices that re-engage with the tradition of political documentary: a terrain that again opens onto the conversation with Martha Rosler.

B. It provides us with a historical framework for thinking about the meaning of a development such as Chantal Akerman's From the Other Side (2002), a film installation for 18 monitors and two screens, real time video broadcast, Super 16 and video transferred to DVD.

A. The medium description itself is a catalogue of new technology...

B. The 18 monitors screen footage of Agua Prieta, the Mexican town where, Akerman writes in her catalogue text, 'one waits to get over to the other side... an ante-chamber of the United states' where both Mexican and Americans are implicated in the business of border crossing. But what are we to make of the real time video transmission from the border? What does it mean for the museum visitor to wait in front of the screen in anticipation of watching someone attempting to cross?

A. It draws attention to an important political situation in, to use Ottinger's phrase, one of the 'blank spots' on the map of the world today. At the same time though, it implicates us is structures of surveillance, and unequal power relations.

B. I am posing a question about relations between the aesthetics and ethics of making and viewing. The aesthetics of real time video in an exhibition of contemporary art really pushes us to the limit of the old questions about the status of representation and narrative; what we used to call 'the politics of representation'.

A. ...and the grand rhetorical flourish is tempting: with real-time video, the time of history is now.

B. Well let's resist the grandiose, unanalysed, untheorzised statement in favour of a return to the situation on the ground at Platform5, crystallized in my encounter with Ottinger's installation and your roll call of new technology in the catalogue entry for The Other Side. We want to register an absence in Platform5 precisely in terms of the idea of a politics of non-ambiguity. This concerns the situation of the contemporary artist vis-a-vis networks of global art production, circulation and consumption. Absent from the exhibition, but curiously included in the catalogue essay by Molly Nesbit entitled 'The Port of Calls' is a black and white reproduction of an image, Untitled (J.F.K), 1990, from the series In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyer 1983-94 by Martha Rosier. I work from this work a lot in its form as a book – a gift – for studio teaching. 'Air transportation', writes Martha Rosier in her essay in the book, 'has achieved its present, central role because business and tourism demand it': She is frank about the fact that the business of being an artist demands it. "In the Place of the Public: Observations of a frequent flyer" delineates a series of spaces which play a major role in supporting the global art world. In supporting exhibitions like Documenta, amongst all else that it is, a site of cultural tourism 'When I became something of a frequent flyer', Martha Rosier writes:

I felt like a displaced person, wandering or hurrying through a world made by someone else, for someone else... I continued to take pictures when I was travelling, especially in the terminals, pushing my baggage cart; I was often tired, sweaty, overburdened. I gave the project a phenomenological dimension with words and phrases that indexed my observations and experiences. I also provided a baseline of landmarks and forms of organisation that have governed our lives and institutions. ln a time in which production in advanced industrial societies is increasingly characterized by metaphors of transmission and flow, I am interested in the movement of bodies through darkened corridors and across great distances but also in the effacement of the experience of such travels by constructs designed to empty the actual experience of its content and make it the carrier of another sort of entirely the totalised industrial representation of air travel and its associated spaces as "a world apart".

A. In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyer is clear thinking about the experience, many, probably the majority of people endured to visit Platform5 or even to any of the other platforms so strategically remapping and linking centres of history and thought. The work of In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyer lies at the intersection of the life world and the artworld. For artists and intellectuals who are included in the relations of production and consumption of the global exhibitions, more and more of this world apart is the location and situation of their practice.

B. In Art Forum’s round table discussion of the Global Exhibition, Martha Rosler made a critical point — that the new terms of engagement may be ‘geopolitical, but the work of the “First World” must have a powerful aesthetic surplus or a semantically unrecognizable political dimension in order to gain access…”geopolitical” can have the cover of a prefix to disguise its political nature, but the politics in question had better be far way’. In In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyerthe politics are very close in a way that is profoundly feminist in the nature of its attentiveness to situation, embodiment and politics of both and further, in its function as monitor of the nature of the global art world's support structures, which are fundamentally "First world". So, for me, Martha Rosler's project is really one of one of those puzzling omissions from Documenta XI.

B. This takes us back to the interview with Gayatri Spivak in the book for documenta X.

A. There are three instances in Spivak's text that for me give it the status of a transition between the projects of Documenta X and Documenta XI and explains why these omissions matter. The first one is when she talks about how she stopped being a 'trained colonial subject' because of feminist politics that emerged in a sequence of texts culminating in 'Can the Subaltern Speak?' in which the particular case of one woman who killed herself in the family was 'put over and against the grand philosophers'. (763) An example of feminist politics as the necessary situatedness of a critical/philosophical practice.

A. Then Spivak talks about the relation between what she understands as the political and the poetic:

But what you are talking about, the political and the poetic, I would want to understand it precisely as the relationship between calculus of rights and the mysterious open terrain of learning to respond to the other in such a way that one calls forth a response. The first is a calculus, the political is a calculus. That is why class must remain. But one must make it play, and when one makes it placy then the 'e' comes in. That is when you loosen not just the rights but responsibility in this very peculiar sense: attending to the other in such a way that you call forth a response. To be able to do this is what I am calling the poetic for the moment, because that brings in another impossible dimension, the necessary dimension of the political. That for me today is the most important thing. That is why I can talk about a suspension of analytical - not throwing away of the analytical, but another way of learning dialogue.

(Spivak, 1998: 768)

B. It is this kind of knowing suspension of the analytical that characterises the best new work in Documenta XI and links with the holding open function of this not-quite documentary-not -quite distanciation and indexical in the formal sense of carrying the imprint of both those conventions, quality that I keep trying to describe in the Ottinger film.

A. So what we are getting at is that Documenta XI takes these things on board structurally but without ever acknowledging their existence in Documenta X and as a long-term feminist informed practice. Not that they should have, necessarily; although forgetting is as political as ignoring. We can and have tried to allow these rewoven threads of varied related histories into the script as part of our genealogical work.

References

1

Jean-Paul Ameline, Face à L'Histoire (Paris: Centre Pompidou et Flammarion, 1996).

2

Zygmunt Bauman, In Search of Politics, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999).

3

Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts (Boston and Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

4

Jean François Chevrier, 'Interview with Gayatri Spivak,' in David, Catherine and Chevrier, Jean François, Documenta X: Pol(e)itics (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 1998).

5

Catherine David and Jean François Chevrier, Documenta X: Pol(e)itics (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 1998).

6

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

7

Okwui Enwezor, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash and Octavio Zaya eds., Documenta 11_Platform 1 Democracy Unrealized (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2002).

8

Okwui Enwezor, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash and Octavio Zaya eds., Documenta 11_Platform 2 Experiments with Truth (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2002).

9

Okwui Enwezor, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash and Octavio Zaya eds., eds., Documenta 11_Platform 3 Creolite and Creolization (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2002).

10

Okwui Enwezor, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash and Octavio Zaya eds., Documenta 11_Platform 4 Under Siege: Four African Cities (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2002).

11

Okwui Enwezor, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash and Octavio Zaya eds., Documenta 11_Platform 5: Ausstellung/Exhibition (Ostfilderen-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag and New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2002).

12

Jean Fisher, 'Contaminations,' Third Text, 32 (1995), pp. 3-8.

13

Paul Gilroy, Between Camps: Nations, Cultures and the Allure of Race, (London: Allen Lane, 2000).

14

Donna Haraway, 'Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,' in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, (London: Free Association Books, 1991), pp. 183-201.

15

Frederic Jameson, 'Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism' New Left Review, no. 146 (July-August 1984), pp. 59-92; reprinted in Postmodemism or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (London: Verso Books, 1991).

16

Mark Nash, Experiments with Truth (Philadelphia: The Fabric Workshop and Museum 2005).

17

Nelly Richard, 'Postmodernism and Periphery' and 'Art in Chile since 1973', Third Text, no. 2 (1987/88), pp. 5-12, 13-24.

18

Martha Rosier, 'Lookers, Buyers, Dealers and Makers: Thoughts on Audience,' [1979] Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings 1975-2001, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006), pp. 9-52; Rosier, Martha in Griffin, Tim, 'Global Tendencies: Globalism and the Large-Scale Exhibition', Art Forum, November 2003.

19

Trinh T Minha, Woman, Native Other, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1989).

20

Catherine de Zegher ed., Inside the Visible: an elliptical traverse of twentieth century art in, of and from the feminine. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996).