Chapters

- Back to Top

- IntroductionIntroduction

- Entering the World of Documenta11Entering the World of Documenta11

- Joy, Optimism, Trust, Shared MomentsJoy, Optimism, Trust, Shared Moments

- Breathing Documenta11Breathing Documenta11

- Chohreh FeyzdjouChohreh Feyzdjou

- On KawaraOn Kawara

- Tania BrugueraTania Bruguera

- Thomas HirschhornThomas Hirschhorn

- ReflectionsReflections

- References

Breathing Documenta11 In and Out

Introduction

In his introductory text to Documenta11’s Platform5 catalogue, Okwui remarked that its discursive drive would “[…] never see its conclusion in the spectacular spaces filled with art projects that the exhibition offers to visitors in Kassel”. Rather, he suggested to read the exhibition “[…] as an accumulation of passages, a collection of moments, temporal lapses that emerge into spaces that reanimate for a viewing public the endless concatenation of worlds, perspectives, models, counter-models, and thinking that constitute the artistic subject”1.

Today, almost twenty years later, Documenta11 still does not see its conclusion. Not only because it still reverberates on a personal level. But because, in its decision to step out if its own territoriality – institutionally, discursively and geopolitically – it seriously opened up for and demanded ethical and intellectual reflection on our post-colonial heritage and still dominant Western epistemologies. This process is indeed not concluded, and probably (or hopefully) never will be. There still is so much unrealized, unresolved, not reconciliated, still to be worked on. As Okwui himself noted, Documenta11 happened at the beginning of a not so promising twenty-first century.2 It does not look any more promising today, when various global crises (civil, health, environmental and climate, political, to name a few) impact the majority of the world population on an everyday basis, while it is evident that the impact’s gravity is heavily dependent on our own situatedness. We are more than ever confronted with images and metaphors that show us that we live in a world of proximities, where margin and centre reciprocate, and where politics literally impact every step we take.

How can we then step outside and reflect on processes we are entangled with? How do we negotiate, empathize, reconciliate and practice living together? Through my personal entanglement with Documenta11, then working as curatorial assistant, I aim to lay out how this was made possible. Attempting to avoid being nostalgic or glorifying in this process, I intend to give an account of how the project of Documenta11 not only became a seminal part of close to two years of my life, but also how it physically and literally made worlds meet and collide on a human scale – theoretically and practically, artistically and curatorially, aesthetically and politically, publicly and privately, locally and globally. I will do this by highlighting selected aspects of what it meant to be physically immersed in the project of Documenta11 and in particular the exhibition, but also how Documenta11 influences my practice to this day.

Entering the World of Documenta11

My way to documenta was in a way typical for a young, female and recently graduated art history student trying to orientate herself in a field that was largely (and to a large extent still is) impermeable: through coincidences, conversations, and internships. I had met one of the former directors of the documenta archiv, Dr. Konrad Scheurmann, at a seminar in November 2000.3 In our friendly conversation I must have clearly signalled where my interests lay and that I was neither afraid to move to an (to me) unknown place nor prepared to start working at the bottom of the art hierarchy. It resulted in Dr. Scheurmann’s kind offer to support the possibility of an internship at Documenta11. It led to my first encounter with Okwui and the project manager, Dr. Angelika Nollert (hereafter called Angelika), during an interview in January 2001. The internship became reality one month later and resulted in a “permanent” position as curatorial assistant in Kassel until October 2002. It was the beginning of a journey that opened up for alternative worlds of knowledge, that forged friendships and professional relations, that created kinships between people as well as with the artworks that materialized in the exhibition of Documenta11.4

Joy, Optimism, Trust, Shared Moments

The notion of joy receives very little attention in the field of art, neither in regard to how it can be an important drive to work together and communicate your cause, nor in relation to the affective qualities of the art object. Optimism cannot be equalled with joy. But it is connected to joy as an inner emotional drive to have a positive outlook on the world and its future. Okwui embodied both inner joy and optimism, and he managed to transmit these to the people he chose to work with. Okwui enjoyed life, enjoyed good company and distinguished conversations, enjoyed good food (his personal assistant Andreas always had his hands full in finding the best places to go to). It was surely no coincidence that during the installation phase the middle section of documenta-Halle was turned into a large canteen for all the artists and the team, and thus became an important social and informal meeting place where we could exchange experiences, ideas, challenges, solutions or simply enjoy being together.

Apart from joy and optimism, there were also other elements that would push us forward: mutual trust, perseverance, even frustration, shared moments. Perhaps one of the most intense shared moments was when we jointly witnessed the planes flying into World Trade Center on September 11 live on TV. The news had spread like wildfire in the offices (despite being in the pre-smartphone era), and soon the team crammed in the building’s only place with a TV, the janitor’s room. I remember a tiny box TV we all stared at in utter silence, still unsure if what our eyes saw was really true. Okwui, too, stood there, among us, without words. No image from this situation exists, but to me it eerily invokes an image that circulated the media as a consequence of the attack almost ten years later: that of the Situation room which shows then President Obama, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden and other officials staring at video footage pronouncing the death of Osama Bin Laden. There we stood and sat watching the September 11 attacks and felt how politics and world events had affected our bodies, trying to understand its causes and its effects, trying to establish connections. I imagined that this event was one of the hardest to confront in the process of curating the exhibition of Documenta11. On the one hand it played so much into the discursive debates and artistic projects, and on the other it was too recent and large to grasp. Touhami Ennadre’s photographs were the only direct reference to that event in Documenta11.

Breathing Documenta11

It is impossible to create a distance between Documenta11 and myself when giving an account of experiencing the exhibition. On the contrary, Documenta11 came as close as it could: by fully entering my body. It meant being alert day and night; weekdays, weekends and holidays; before, during and even after the exhibition period. In short, breathing documenta in and out. Surely, this was also connected to the circumstance that the majority of the Documenta11 team was not from Kassel, which meant that there was no local social network to rely on. Instead, the team relied on each other, we were all in the same boat (see illustration 1, Andreas Seiler’s humorous take on what it meant to sit in the Documenta11 boat, or in this case car).

© Courtesy Andreas Seiler

But above all, it was the intense collaborations with the artists and their projects that influenced this condition. This possibility, however, was not a given. Okwui and the project manager Angelika had decided to entrust the four persons working in the artistic office to be the main contact for each invited artist (Renée Padt, Luise Essen, Angelika and myself). We became the steady nodal point between curators and artists, artists and installation team/architects, artists and external collaborators. We slipped into the role of mediators, facilitators, organisers, producers, translators, fundraisers, negotiators, confidants, supporters, companions, guides, co-hosts, mouthpieces. Thus, my experience of the exhibition is closely connected to the artistic projects I was mainly responsible for, while being fully aware that mutual trust between Okwui, his co-curators, the project manager and myself was the pre-condition for this possibility.

My account gives small but hopefully noteworthy insights into aspects of projects that usually remain invisible when mediated to the public (both by the institution and externally). Exhibition publications for example are usually finalized before the projects have fully materialized in the exhibition space. Texts on the artworks are therefore to an extent also a speculation on the outcome of an artistic project. Additionally, often material related to the process of exhibition-making gets lost because staff is temporarily hired, works under time pressure and is rarely occupied with archiving self-generated documents unless it is contractually obliged to do so. A lot of material is also ephemeral. Conversations, correspondences and informal meetings are often not recorded or meticulously protocolled. From an external perspective, press articles and reviews conventionally mediate an exhibition as a finished project and aim to provide an overall view, rather than investigating the process of exhibition-making. Platform6 is therefore a unique opportunity to share insights and experiences into Documenta11 that otherwise would be lost. At the same time, my account inevitably contains reconstructed memories which however simultaneously indicates that these still have an impact.

Chohreh Feyzdjou

Chohreh Feyzdjou’s installation occupied one of the central spaces in the Museum Fridericianum. It consisted of multiple shelves housing sealed glass jars, drawers with hundreds of small hand-formed wax objects and large racks with rolled up fabric and canvases. All elements were covered in black pigment. The entire installation appeared fragile, like a discarded archive that was slowly disintegrating. It communicated a sense of grief, loss and longing for something that was difficult to grasp, but that appeared to be connected to notions of memory and identity. Chohreh Feyzdjou was an Iranian immigrant artist who had died in Paris in 1996. When the curatorial wish was expressed to exhibit her works at Documenta11, the artist’s legacy was still unresolved. Thus, my loan requests got caught up in the larger negotiations about the works’ location, conservation (which was a large issue due to its fragility) and final destination. I exchanged endless letters with representatives of public French institutions such as the DAP (Delegation des arts plastiques) and the CNAP (Centre national des arts plastiques). Months of correspondence took place parallel to the negotiations that finally secured Feyzdjou’s legacy and which resulted in the acquisition of the works for the collection of the CAPC Musée d'art contemporain de Bordeaux. Only through that decision could we secure the loan, finally having a lender to be addressed. I believe that documenta played no minor role in pushing and accelerating official decisions to acquire and preserve these works for the public good. Okwui insisted that an international public needed to know about the work’s existence. It needed to see and feel how it embodied a woman’s personal stories of migration, loss and search for identity, and how these universally resonate with us.

On Kawara

Although On Kawara’s One Million Years (Past and Future) did not lie under my overall responsibility, my colleague Luise Essen and I were assigned to organize its live performance for the whole exhibition period. At Documenta11, One Million Years (Past and Future) consisted of a custom-made glass vitrine measuring about three by six by three metres in which a man and a woman would sit at a table to simultaneously read out one million years into the past (998,031 BC to 1969) and into the future (1996 AD to 1,001,995 AD). The live reading was transmitted through speakers into the exhibition space, while it was also broadcast via a regional radio channel. Organizing On Kawara’s live performance entailed not only organizing the performance schedule as such, but also the recruitment of its readers. With no budget assigned to this live performance, we had to be inventive to find volunteers. For every day of the exhibition period (100 days) we needed exactly ten male and female readers (each person had to read for one hour, the exhibition hours were daily from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.). In order to make this possible, my colleagues and I had stirred up the PR machinery enormously, tirelessly talking to people in the streets of Kassel about the project, distributing flyers, informing the local media to get support and finally, promising to reward participants with various types of free entrance tickets (depending on the amounts of hours read). Word of mouth did the rest. Thus, what seemed an impossible task at first, turned out to be realizable thanks also to the enormous enthusiasm amongst the population of Kassel. As a result, the live performance would run smoothly and almost uninterruptedly over the course of one hundred days. Behind the scenes, however, One Million Years had become close to a social experiment. Friendships developed and love affairs evolved, animosities and preferences were expressed (some denied reading with others or insisted to only read with a specific person). For some it became a compulsive habit to have “their” regular reading inside the glass vitrine, for others it appeared to be a meditative session. Some looked forward to “bathing” in one hour of fame, where the glass box acted like a stage and allowed exposure to a large audience (while still being somewhat protected inside the vitrine). Others were simply motivated by the prospective of receiving free entrance tickets to the exhibition. One Million Years laid bare human traits and sensibilities. It created interpersonal relationships, but it also showed the effects of being confined (or in this case encased) in a common yet transparent space, where one could be observed and scrutinized.

Tania Bruguera

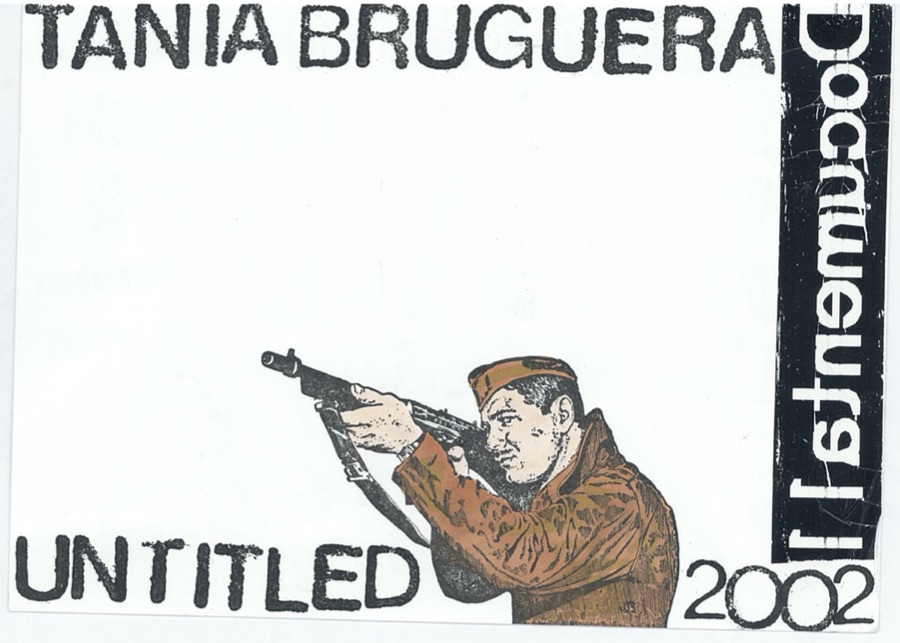

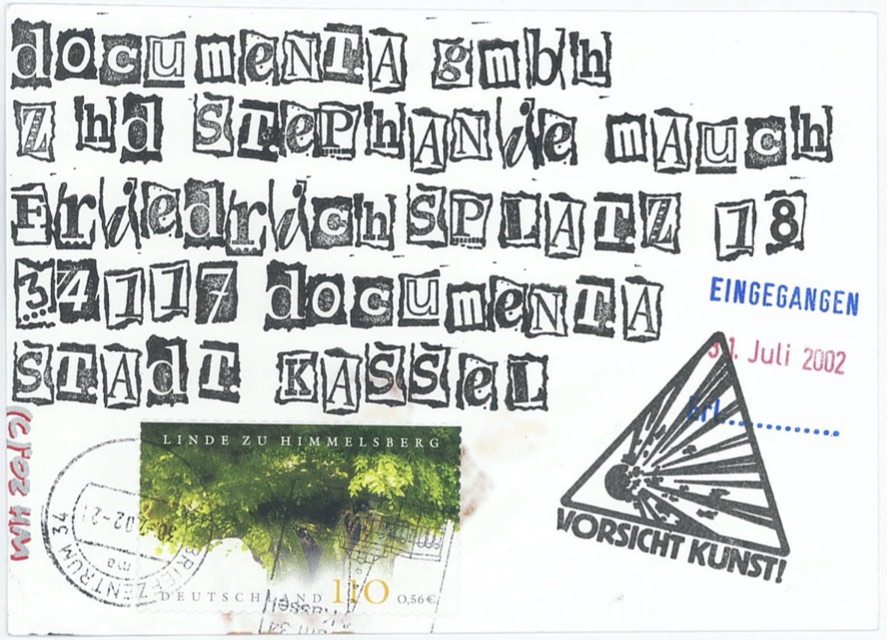

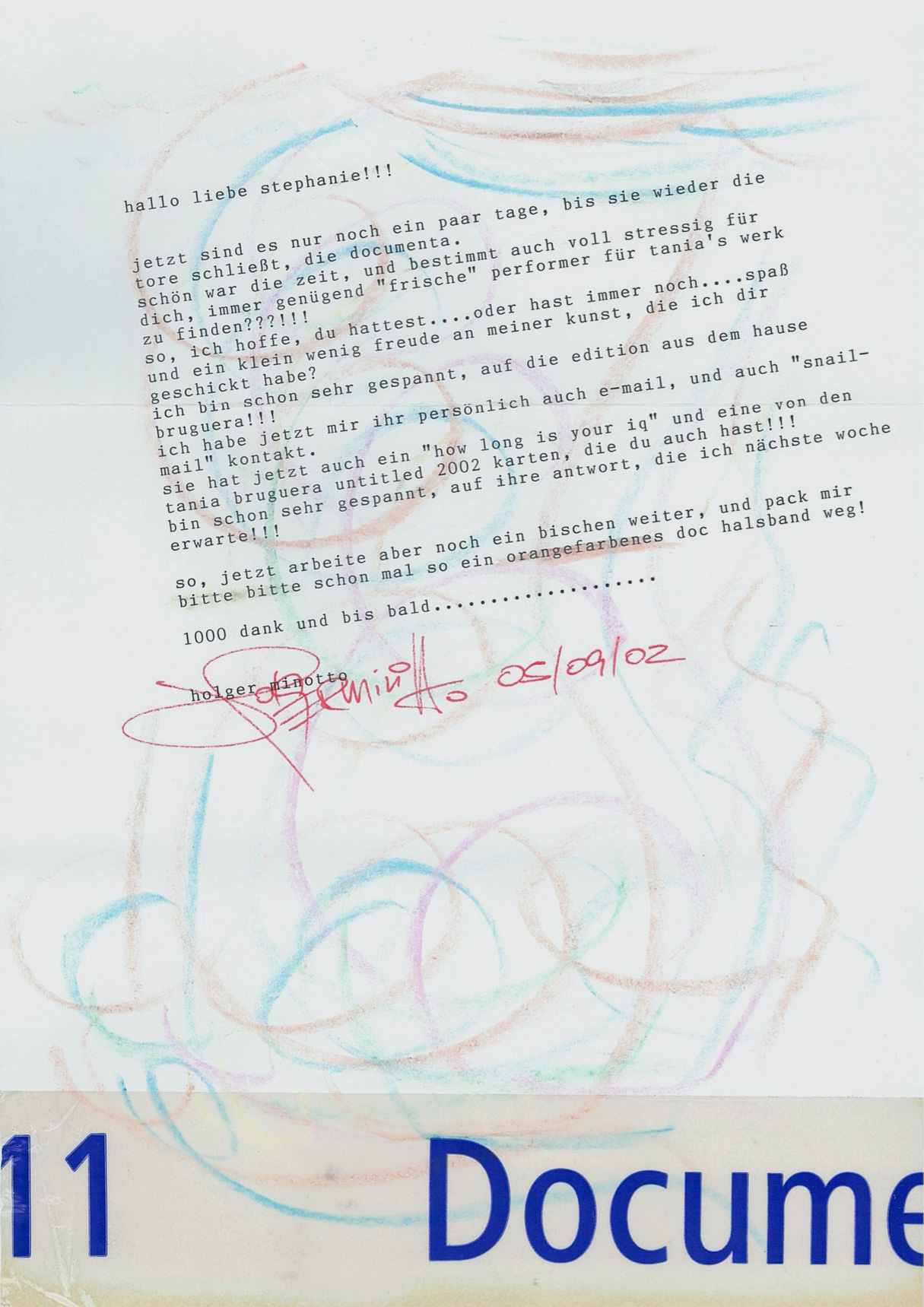

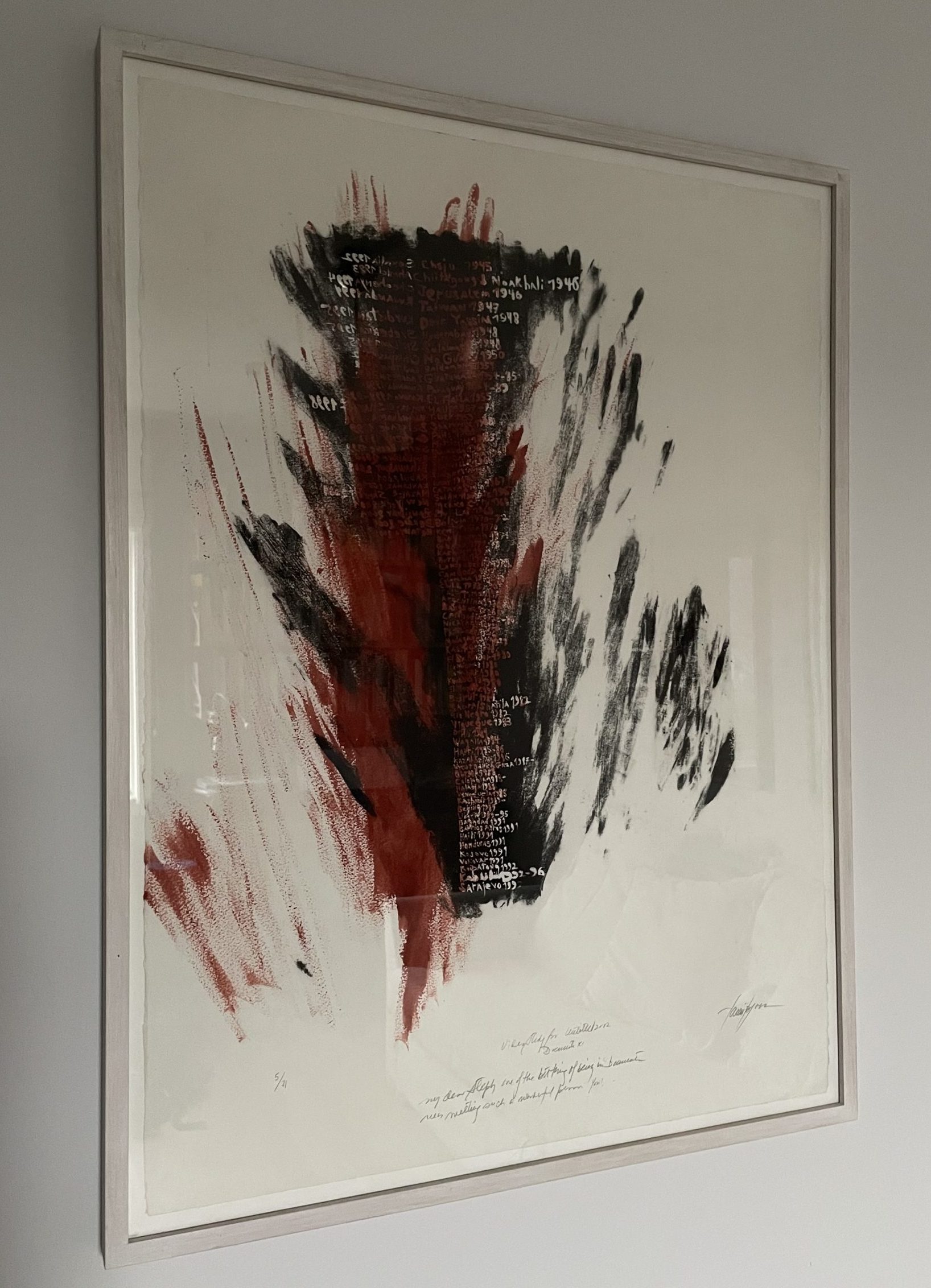

Also, Tania Bruguera’s performative installation Untitled (Kassel) required a large number of volunteers for a live performance during the exhibition period. But in adverse to On Kawara’s One Million Years, I had worked closely with Tania Bruguera over several months on her project. The performance inside the exhibition space was only one (though essential) element of the entire work. Located at the former Binding brewery, where every artist had received his or her own space, Untitled (Kassel) was a multi-medial set up that consisted of a video projection, floodlights, a scaffolding structure that lined two walls of the exhibition space and two live performers. Upon entering the space, the visitor was either blinded by the floodlights or immersed in darkness. When the floodlights were on, one would hear a person nearby assembling and disassembling a rifle while another marched with military boots back and forth on the elevated scaffolding structure. When the lights went off, the activities of the performers stopped. Suddenly no longer sound or light would affect the bodily senses, but the deprivation of such. Only through time could the eyes slowly adapt to the darkness and make out a large video projection on a wall. In the video, the viewer observed a shadowy figure running away. The unsettling scene was super-imposed with a global list of place names where massacres and genocides had taken place since 1945. In using 1945 as the earliest historical reference, Bruguera subtly referred to the history of Kassel as an arms manufacturing centre during WWII but also pointed to the responsibility and hypocrisy of the arms industry in relation to these events. Both run-away scene and place names continuously looped in the exhibition space and only “disappeared” when the floodlights illuminated the space again and the performers resumed their activity. The assembling and the disassembling of the rifle in fact required strength and special training, while the heat generated by the floodlights left the performers often exhausted. As a result, performers rarely managed to be inside the space for longer than one hour per day and we were completely dependent on a large number of strong and trained volunteers. Also here a group of enthusiasts formed around the project (illustration 2), not least thanks to Tania’s continuous personal involvement. Tania had namely promised to reward the performers with a series of lithographs at the end of the exhibition period. Depending on the number of hours performed, Tania would reward each performer with up to six lithographs (illustration 3).

© Courtesy Stephanie von Spreter

© Courtesy Stephanie von Spreter

© Courtesy Stephanie von Spreter

© Courtesy Stephanie von Spreter

© Courtesy Stephanie von Spreter

© Tania Bruguera / Photo: Stephanie von Spreter

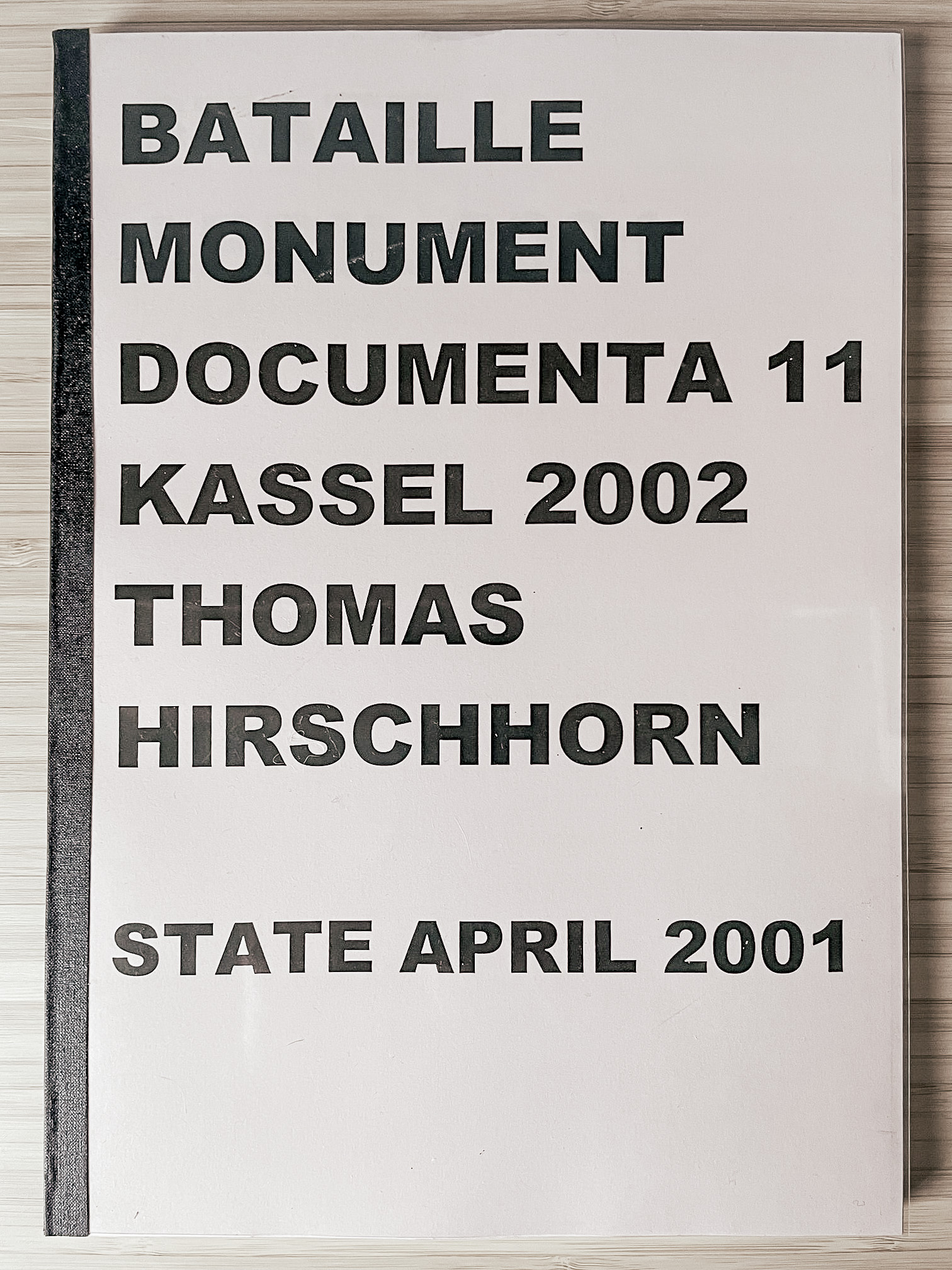

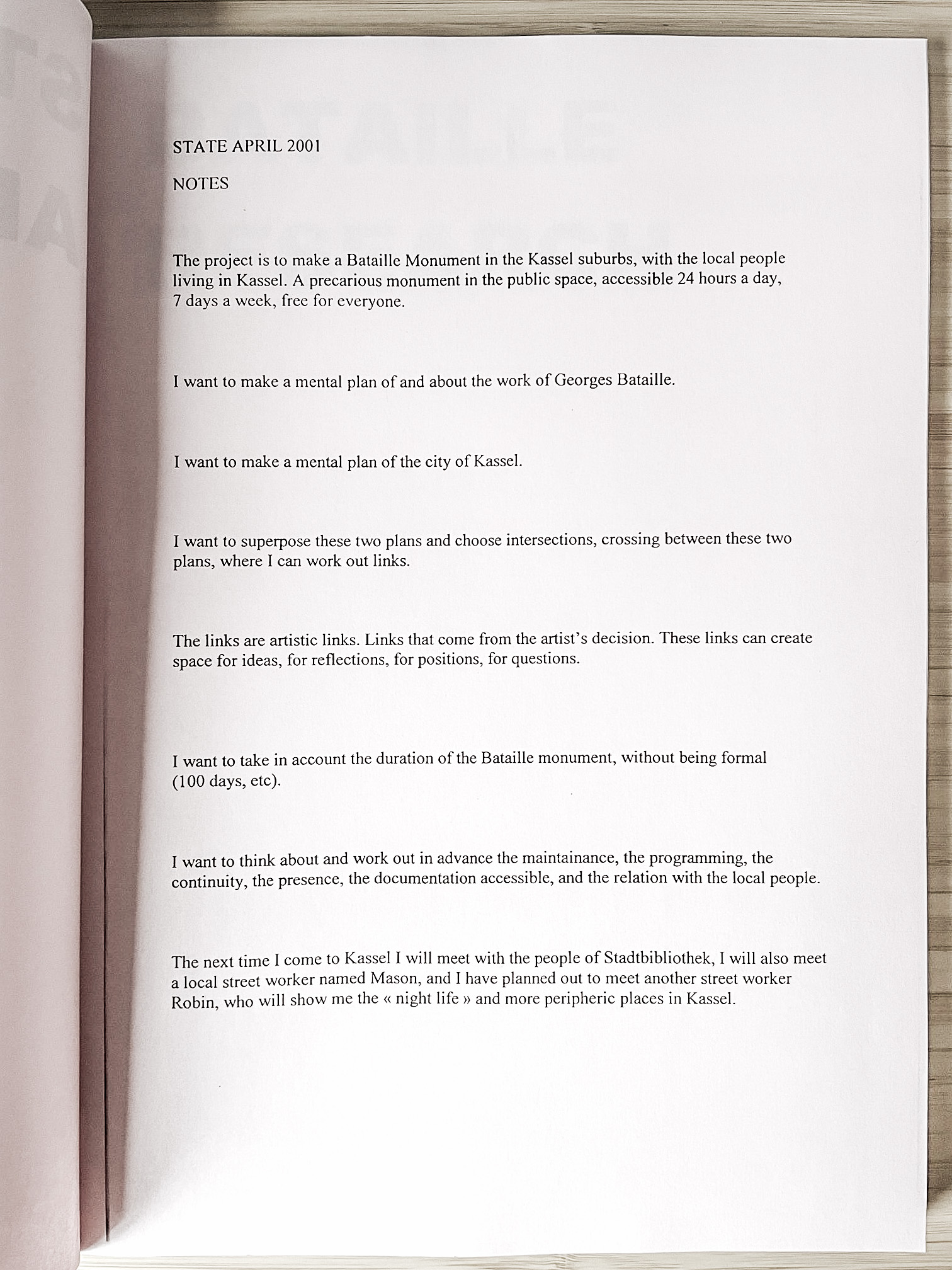

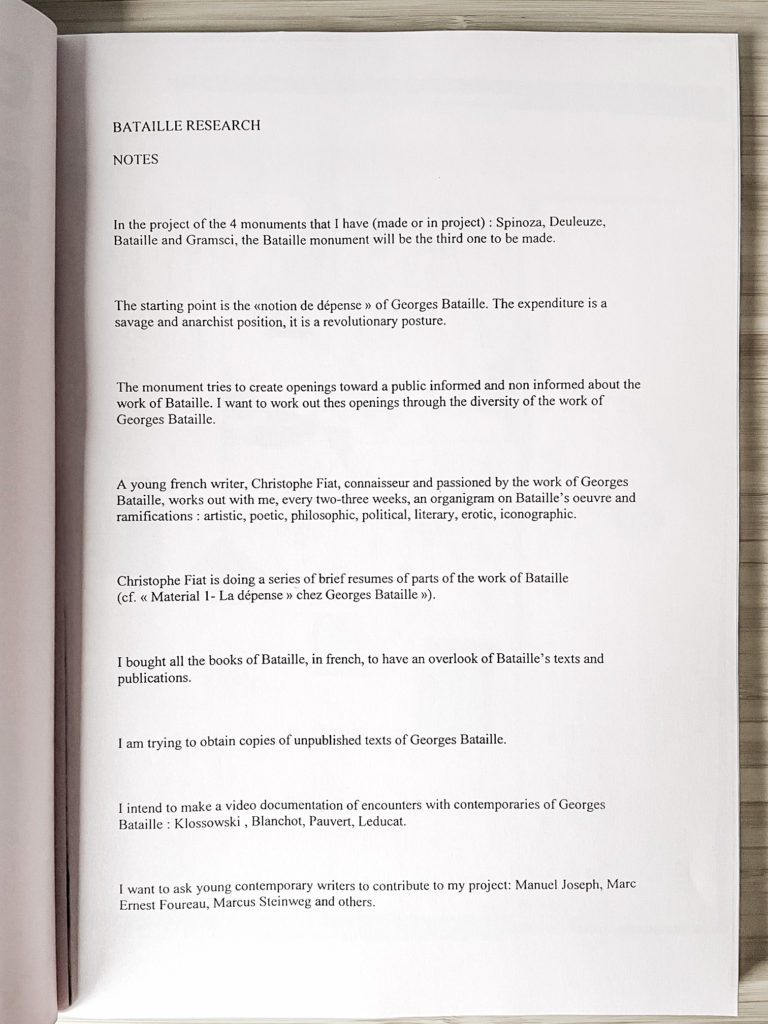

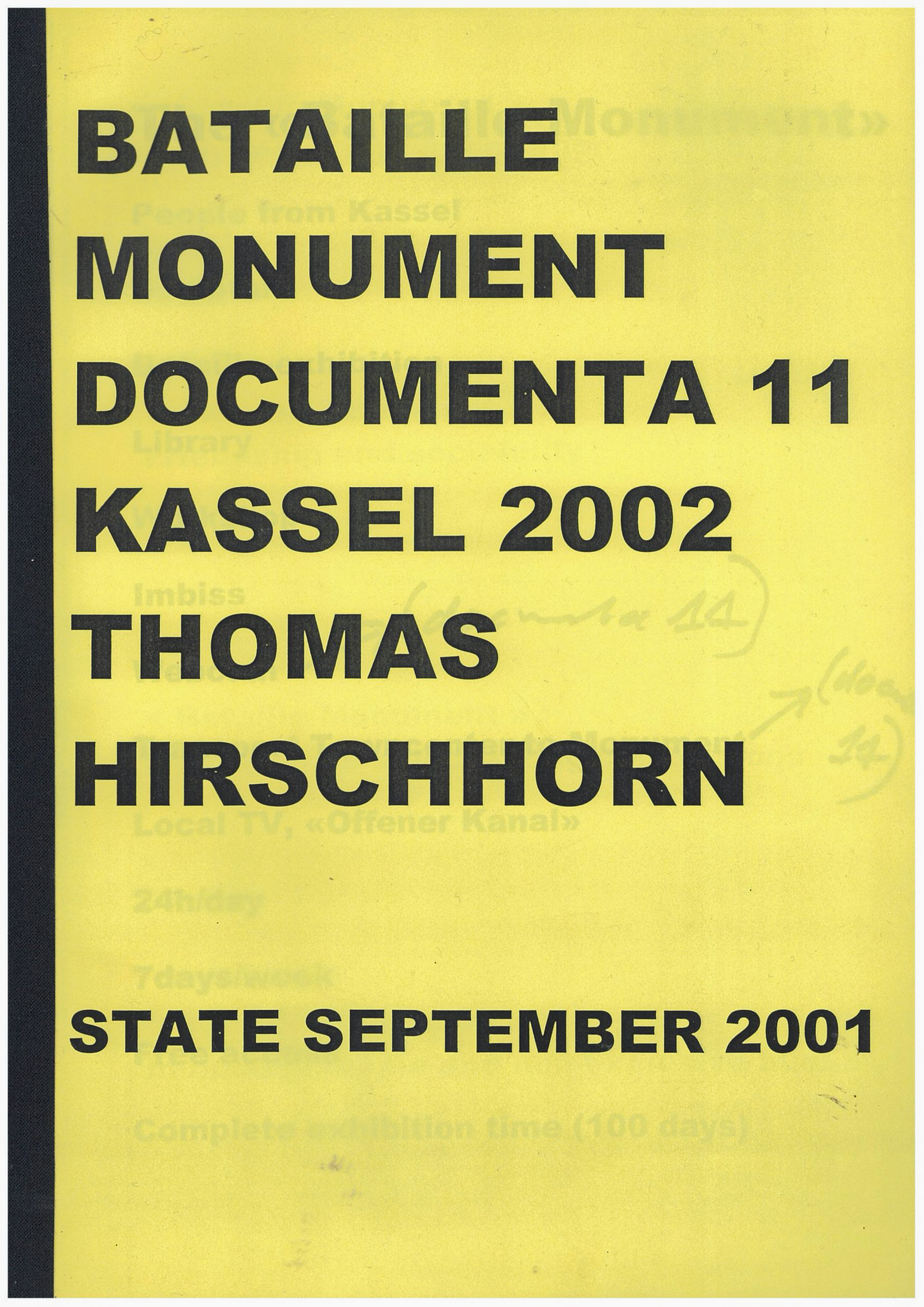

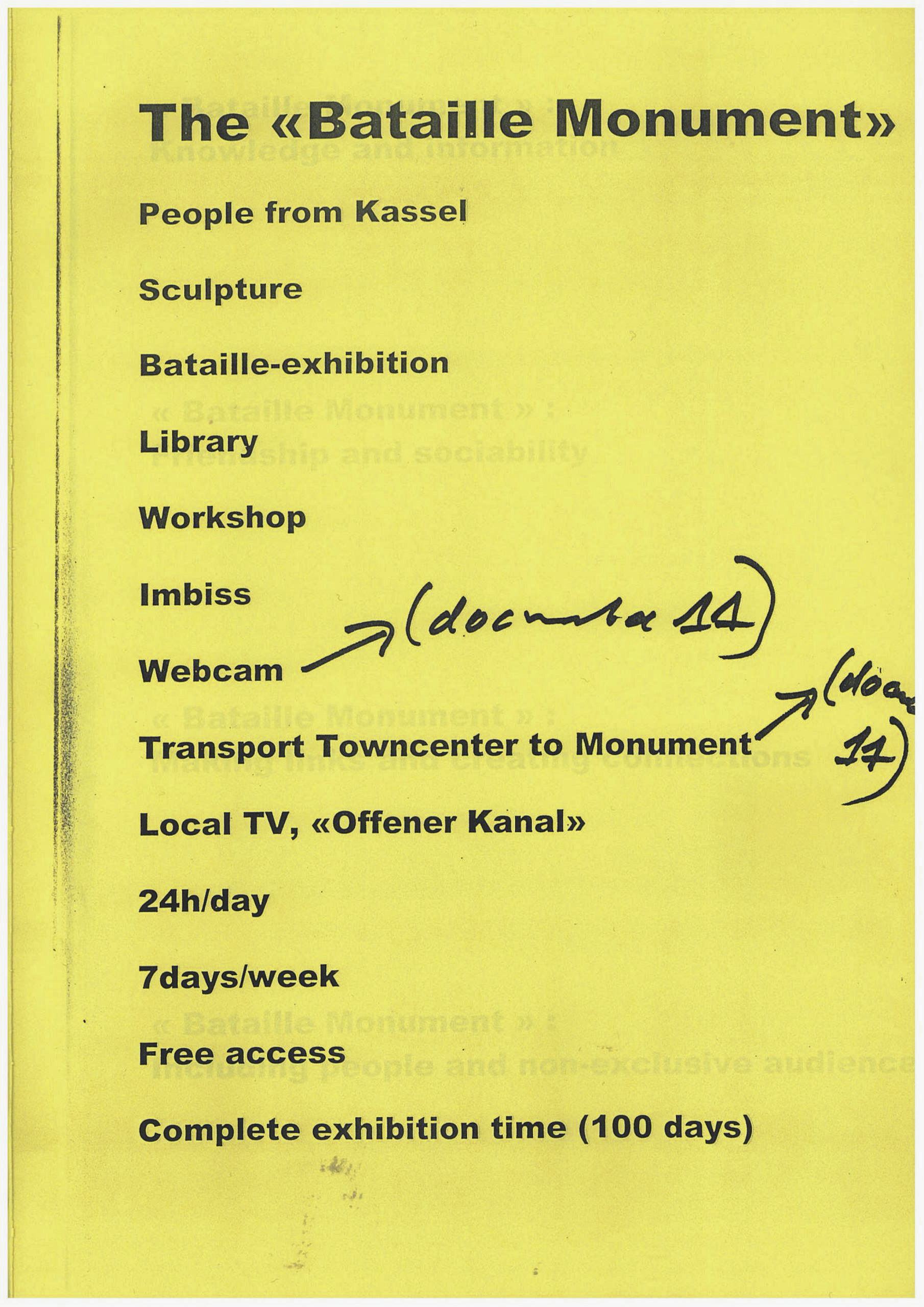

Thomas Hirschhorn

One of my closest artist collaborations was with Thomas Hirschhorn to support him in the production of his Bataille Monument. However, the monument’s complexity and its long-term formation process as well as Thomas’s independent way of working make it impossible to comprehensively describe and reflect on the monument here. I will thus pick two anecdotes from our collaboration – which Thomas hopefully forgives me for disclosing. These anecdotes in fact are illustrative examples of Thomas’s endless dedication and energy in materializing the Bataille Monument in a peripheral area of Kassel (the Friedrich-Wöhler-Siedlung) marked by high unemployment rates and inhabited by a large number of low-income migrant communities. They also expose the challenges Thomas met during his work, often pushing his own limits – and all the time those of art and art-making itself. They also show how his practice became political, without becoming politicized.

One of the monument’s elements was a snack bar (“Imbiss”) housed in a wooden, makeshift structure similar to the library, TV station and Bataille exhibition. The “Imbiss” on the one hand invited the local population and external visitors to stay and dwell in the area, to provide food and to become a social meeting place. On the other, it was Thomas’s wish that the “Imbiss” should be run locally by a community of older migrant women. As a result, these women would obtain an income and a degree of independence and empowerment. But to run an “Imbiss” was easier said than done. It not only required prior permission by the public authorities but also entailed that the “Imbiss” was subject to random official checks about hygiene and food safety. One day I received a nervous phone call from Thomas asking me for help. The health authorities had indeed been there to check and had demanded to inspect the “Imbiss”. Thomas, however, termed the “Imbiss” part of his artwork and denied entry. The situation had escalated. The authorities threatened to close the “Imbiss” and call the police because they suspected it would not meet hygienic standards. Thomas was furious; for him it was no option to close down such a vital element of his monument, while for the authorities it was no option to allow the “Imbiss” to operate without approval. I arrived a few minutes later as a mediator. Finally, we reached the agreement that the “Imbiss” could be inspected on the condition that Thomas would not be present but that I would act on his behalf. In the end, with a few amendments and proposals by the authorities, the “Imbiss” was allowed to operate again.

Those who physically visited Documenta11 hopefully grabbed the opportunity to use the “Fahrdienst” (shuttle) to get to the Bataille monument. Also, here Thomas was persistent that the drivers were recruited from the Friedrich-Wöhler-Siedlung and that they were paid for their work (which Thomas covered, in addition to acquiring and fixing the cars and petrol). Equally here some preconditions had to be met. First the cars needed to pass the TÜV to meet all vehicle and safety regulations. Then a vehicle operating license had to be obtained. Furthermore, drivers had to have a valid driver’s license and a police certificate of conduct. Thomas worked with many teenagers and young adults, many of them through his collaboration with Lothar Kannenberg and his Boxcamp Philippinenhof (Boxcamp was a social youth project that aimed at re-socializing criminalized youths, amongst other things through structured routines and physical exercise like boxing). Many of the potential young adult drivers could not easily provide both. But Thomas incessantly defended their ability to commit to this job. Finally, we managed to obtain all necessary licenses. The “Fahrdienst” had, one could argue, become a re-socializing project in itself. But this surely is not how Thomas saw it. For him, the “Fahrdienst” was, like all the other elements of the Bataille Monument, part of his artistic practice and part of the artwork. An artwork with a political impact, an artwork that created social bonds and provided knowledge. An artwork that was deeply democratic in being communal and inclusive, and one that allowed and asked for participation and interaction (Illustration 4).

© Thomas Hirschhorn / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

© Thomas Hirschhorn / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

© Thomas Hirschhorn / VG Bild-Kunst , Bonn 2025

© Thomas Hirschhorn / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

© Thomas Hirschhorn / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

© Thomas Hirschhorn / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

As I see it, the Bataille Monument embodied, even demanded, an act of emancipation. In that sense it met one of Rancière’s proposals to emancipate the spectator: to turn the “spectator” into a participant, abolish the distance between performer and audience to be drawn into the circle of magic action.5

Reflections

Rancière’s other proposal to emancipate (and thus activate) the “spectator” is to make her/him identify with the subject matter. Okwui and his co-curators profoundly showed us how this is possible, both by revealing that the artworks derive from specific contexts and realities, and by establishing connections through their curatorial or discursive contextualization. They also showed that this is possible when believing that the “spectator” is not ignorant or uninformed but intellectually and emotionally capable of associating, comparing, translating and relating. As Rancière says: “Like researchers, artists construct the stages where the manifestation and effect of their skills are exhibited, rendered uncertain in the terms of the new idiom that conveys a new intellectual adventure. The effect of the idiom cannot be anticipated. It requires spectators who play the role of active interpreters, who develop their own translation in order to appropriate the ’story’ and make it their own story. An emancipated community is a community of narrators and translators”.6

This approach was felt throughout platform5. The curated artworks stirred up my senses, my beliefs, entire world views. Documenta11 kickstarted a decolonization process asking us to critically re-evaluate history and making us realize that the post-colonial is inside of each of us. Through its discursiveness, Documenta11 also managed to “liberate” specific mediums from its autonomy, to me foremost the filmic and photographic: works with documentary features entered the exhibition spaces while making aware of their poetic qualities; films conventionally confined to the cinema were given the space to expand; photographs previously not circulating in the art economy were considered for their aesthetic, discursive and political relevance. I remember the first time I saw Amar Kanwar’s A Night of Prophecy in its pre-post-produced version. I was deeply moved about the story that Amar unpacked before my eyes, turning me into a witness while also immersing me in the songs that communicated protest, loss and melancholy. Equally, Zarina Bhimji’s Out of Blue, Isaac Julien’s Paradise Omeros, Igloolik Isuma Production’s Nunavut (Our Land), Black Audio Film Collective’s Handsworth Songs, David Goldblatt’s, Allan Sekula’s and The Atlas Group’s photographs were powerful visual stories that still resonate with me.

The photographic medium and its ability to enter, visualize and communicate different worlds and world views has accompanied me since, both in my previous curatorial practice (directing a non-profit space for contemporary photographic art until 2018) and in my current critical practice as a PhD fellow at UiT the Arctic University of Norway, which is anchored in a research group called Worlding Northern Art. One of the group’s aims is to operate in the contact zone between different academic disciplines, curatorial practice and artistic research. Now that I look back and reflect on Documenta11’s platforms, I can detect parallels to this approach. In addition, my research is done in the belief that the (circumpolar) North is not marginal or that it is not taking place at the edge of the world. Rather, by looking at commonalities such as climate and climate change, identity and (colonial) history through art, connections to other parts of the world are established, not least because the region is considered seismic for planetary climate change but has also been subject to conquest and Imperial endeavours, while it still holds geopolitical importance. Worlding northern art is about establishing relationships and investigating how cultural practices make worlds that let other voices speak – such as in my research that looks at photographic art that engages with the Arctic as a gendered, colonial and ecological space. And again, Okwui’s words reverberate in this context, even if he spoke about the exhibition of Documenta11: ”The exhibition as a diagnostic toolbox actively seeks to stage the relationships, conjunctions, and disjunctions between different realities: between artists, institutions, disciplines, genres, generations, processes, forms, media, activities; between identity and subjectification. Linked together the exhibition counterposes the supposed purity and autonomy of the art object against a rethinking of modernity based on ideas of transculturality and extraterritoriality. Thus, the exhibition project of the fifth Platform is less a receptacle of commodity-objects than a container of a plurality of voices, a material reflection on a series of disparate and interconnected actions and processes”.7

References

1

Okwui Enwezor, “Black Box”, in Documenta11_Platform5: Exhibition Catalogue (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2002), p. 42.

2

Ibid., p. 43.

3

The seminar was arranged by AXA Art Insurance Cologne for recently graduated art historians to provide information on different job opportunities in the field of art. Dr. Konrad Scheurmann was one of the speakers.

4

In reference to Haraway’s proposal of making kin. See Donna Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene”, (Durham, North Carolina, London, England: Duke University Press, 2016).

5

Jacques Rancière, “The Emancipated Spectator”, in Le spectateur émancipé (London: Verso Books, 2009), p. 1-23.

6

Ibid., p. 22.

7

Enwezor, “Black Box”, p. 55.